The Gannett/GateHouse deal is even more depressing than I imagined

Great for bankers, shareholders; lousy for consumers, journos

God bless Ken Doctor for having the patience to dig through all this Wall Street posturing and monetary machismo to pull together such clear-eyed analyses of the Gannett/GateHouse merger (acquisition, really, as it turns out).

Few people are better sourced than Ken is on these kinds of stories — and frankly, few journalists understand this as well as he does. Ken Doctor’s coverage of this saga (and the business of the news industry in general) is required reading to anyone who cares about the future of local news.

Ken’s latest on the Gannett/GateHouse merger, I’m sorry to say, may be his most depressing dispatch on the sorry state of the news business yet. If you have not read it, you might just want to queue up a some happy place Twitter feeds as a palate cleanser to get you through it.

Or, I’ll do it for you.

Here’s what struck me: In all the reporting about the ins-and-outs of this merger, I have yet see to how, in the end, this is going to end up serving the needs of local news consumers, their communities or the journalists who work there.

Bankers, lawyers, private equity, executives, shareholders? Check, check, check, check and check. Consumers? Journos? Tk, I guess.

When I read terms like “synergies” and “efficiencies” in relation to deals like this, I know that means weaker local news organizations and fewer journalists on the job. It’s really that simple.

I sincerely hope I am wrong about that, but looking at the dollars-and-cents reality of this merger, it’s hard to see how this ends well.

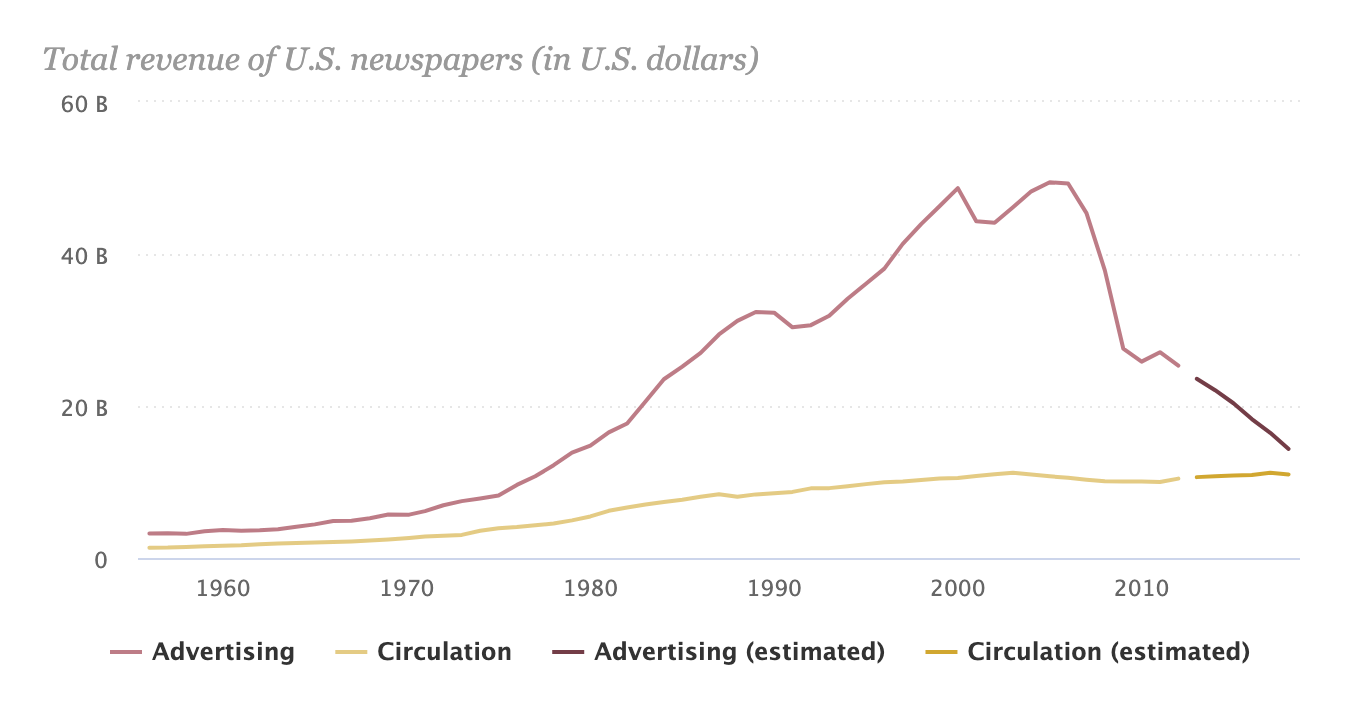

In the salad days of the 1970s and 1980s, Wall Street banks provided the capital to help family-own news companies grow into giant publicly traded national chains. Today, it seems, Wall Street is eating those chains alive. The investment banks have moved on, leaving venture capital to strip what’s left of the big chains for spare parts.

It turns out, for example, the only way the Gannett/GateHouse deal could get financed is through private equity. It wasn’t the best deal, as was originally reported. It was the only deal. No traditional investment bank would touch it.

A quote from Ken’s piece:

“Remember, lots of banks were in on the reviewing deal,” says one significant holder of Gannett shares. “And no one would finance it. It took Apollo and that high rate to get the deal done.”

Let that sink in for a minute, particularly in light of Gannett’s failed attempt to acquire tronc/Tribune in 2016. That deal fell apart after two of the three investment banks involved walked away.

I’m certainly no finance guy (which I will prove repeatedly throughout this piece), but I can’t recall too many times when investment banks have walked away from millions in fees they receive to finance a merger. How bad does a balance sheet have to look for that to happen?

Maybe it’s more common than I realize. But regardless, it can’t be a good sign that a hedge fund was the only one willing to finance it. And at terms that are kind of amazing: a five-year, $1.79 billion loan at an 11.5 percent interest rate. I have personal credit cards better than that.

Speaking of debt, the amount this “New Gannett,” as Doctor dubs it, is taking on is massive.

To make two companies into one, they are saddling themselves with a $1.79 billion loan — more than double the companies’ current combined long-term debt and probably at a far higher interest rate.

That leads to this quote in Ken’s piece:

“That means that for the next couple of years, the New Gannett will be driven to pay off as much of that debt as possible.”

Which makes sense. If the combined company can bring its debt down, it will then be able to refinance with traditional lenders at rates far below 11.5 percent.

My question is, how exactly do they plan to bring the debt down in such a short time?

(Here I issue my standard disclaimer: I covered politics back in the day, not finance. So if I’ve gotten this wrong, please do let me know. But this is based on what I could find in each company’s 2018 10K.)

Combined, the two companies earned $32 million in 2018 on $4.5 billion or so in revenue. They currently hold a combined $800 million or so in debt, on which they pay a combined $60 million or so in interest.

The plan is to swap the old debt with $1 billion more in new debt. If the goal is to pay down a significant amount of principal on that loan, that will mean debt payments will skyrocket. If I borrowed that much money on those terms, my payments would be north of $400 million per year. It’s big.

How do you pay off that much debt and maintain your margins? The answer seems to be “synergies,” which is which is Wall Street Speak for cost-cutting and layoffs.

There are certainly some savings to be had from de-duplication of vendor contracts, things like that. Neither GateHouse and Gannett are companies known to run particularly lavish operations. Which means I think we know where the bulk of the savings will come from.

Here’s the money graph from Doctor’s piece, in my view.

Let’s say things go exactly as planned and those savings do materialize, what will the New Gannett do with that money? As Doctor puts it:

The question is where do these savings go? Think Let’s Make a Deal’s three doors:

* Debt repayment. A must, of course, with that added incentive of getting the principal down for a cost-saving refi.

* Dividend: New Media Investment knows it needs its dividend to keep shareholders happy.

* Reinvestment in the business.

Look no further than the words of Mike Reed, chairman and CEO of New Media Investment Group, the holding company that owns GateHouse. Reed will be CEO of the merged company, and made his priorities pretty clear during a conference call with investors last week.

He said:

“Importantly, cash flows will also allow for aggressive debt paydown with target net leverage within 2 years of close — of below 1.75x EBITDA. We do expect the dividend will grow as we realize synergies and pay down debt. New Media has historically been a strong dividend payer, raising its dividend in each consecutive year from 2014 to 2018, and we think this opportunity presents the combined company, and it puts it in a position to continue that.”

There’s your answer. Not seeing much of a commitment to reinvestment there, which isn’t a surprise given his history.

Since 2013 when New Media took GateHouse out of bankruptcy, the company has been almost single-mindedly focused on acquisitions, cost-cutting and returning dividends rather than building a sustainable digital local news business.

Gannett at least is trying. It now has more than 561,000 digital subscribers, up more than 34 percent year-on-year. GateHouse, which has more titles and about the same overall circulation, has 174,000.

All-in, digital will make up only about 25 percent of the company’s combined revenue. By contrast, The New York Times is closing in on 50 percent. The Guardian is at about 56 percent today.

In short, these are two companies that still derive a huge amount of their revenue from print — GateHouse in particular. They will have a huge debt service nut each year, and there are already hints that the economy might be slowing down.

Based on what we saw during the mortgage meltdown a decade ago, even a mild downturn in the economy during the next few years would mean even steeper declines in print revenue.

Which would mean even deeper cuts necessary to keep the company above water. And, again, I think we know where those cuts would likely come from.

To be fair, Reed did go on to mention on the call that the merger positions the new company for “long-term growth” in order to support “quality journalism.” But it’s pretty clear where those fall on his to-do list.

All of which brings me back to where this started: the local news consumer and the local journalist — neither of whose interests seem particularly well served here.

Reading about New Gannett, I can’t help but wonder what we will be losing once Old Gannett, the company that gave me my first full-time job in journalism back in 1995, is gone.

Some are optimistic that Old Gannett management can transform New Gannett from within. I’m not sure. This feels like two very different cultures to me. Add to that the financials, and I think New Gannett will be forced act differently, like it or not.

Old Gannett was and is a company with a deep commitment to training (particularly around new skills). I went to my first NICAR because Old Gannett paid my way, as it has for now hundreds of journalists over the years. It changed my life.

Old Gannett has had a deeper and longer commitment to diversity than anywhere else I’ve worked. More recently, Old Gannett has been one of the most active participants and supporters of Table Stakes, a four-year-old initiative to drive digital transformation in local news.

I could go on.

Yes, Old Gannett has always run a lean, top-down operation. But the journalistic mission was, and still is, at its core. Old Gannett is a news business, not a business that happens to own newspapers. There’s a difference, and I think we are seeing that difference on full display.